Availability: Amazon, Los Gatos, San Jose, Santa Clara County

Comments from our member, Marilyn Katz

In My Father’s Court is a collection of memoirs, written as short stories, from the perspective of a young boy growing up in Poland at the turn of the last century. The boy is the son of a Hassidic Rabbi and Rebbitzen, and the court he refers to is the Beit Din, held informally in their home. The family’s circumstances become increasingly difficult over time as the political climate gets worse. The boy writes in a personal voice about the difficulties of family and neighbors. His optimisim through these times has served him well.

For an interesting look at the author speaking about himself, watch this brief video showing I.B. Singer talking about his life. The voice of the author is the same as the voice of the writer of In My Father’s Court. Older and possibly, wiser, but the introspective, cautious voice is the same.

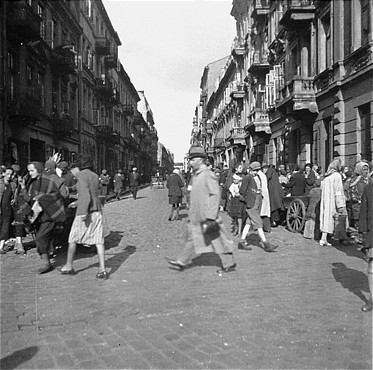

The Zynger family lived on Krochmalna Street in Warsaw. Here are some photos of the area, then and now.

I recommend this book as an introduction to I.B. Singer. He eventually moved to the United States, and became a noted writer. He won the Nobel Prize in 1978 for his impassioned narrative art which, with roots in a Polish-Jewish cultural tradition, brings universal human conditions to life

.

The following speech was given in his honor when he was presented the Nobel Prize.

Presentation Speech by Professor Lars Gyllensten of the Swedish Academy

Translation from the Swedish text

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen,

“Heaven and earth conspire that everything which has been, be rooted out and reduced to dust. Only the dreamers, who dream while awake, call back the shadows of the past and braid from unspun threads, unspun nets.” These words from one of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s stories in the collection The Spinoza of Market Street (1961) say quite a lot about the writer himself and his narrative art.

Singer was born in a small town or village in eastern Poland and grew up in one of the poor, over-populated Jewish quarters of Warsaw, before and during the First World War. His father was a rabbi of the Hasid school of piety, a spiritual mentor for a motley collection of people who sought his help. Their language was Yiddish – the language of the simple people and of the mothers, with its sources far back in the middle ages and with an influx from several different cultures with which this people had come in contact during the many centuries they had been scattered abroad. It is Singer’s language. And it is a storehouse which has gathered fairytales and anecdotes, wisdom, superstitions and memories for hundreds of years past through a history that seems to have left nothing untried in the way of adventures and afflictions. The Hasid piety was a kind of popular Jewish mysticism. It could merge into prudery and petty-minded, strict adherence to the law. But it could also open out towards orgiastic frenzy and messianic raptures or illusions.

This world was that of East-European Jewry – at once very rich and very poor, peculiar and exotic but also familiar with all human experience behind its strange garb. This world has now been laid waste by the most violent of all the disasters that have overtaken the Jews and other people in Poland. It has been rooted out and reduced to dust. But it comes alive in Singer’s writings, in his waking dreams, his very waking dreams, clear-sighted and free of illusion but also full of broad-mindedness and unsentimental compassion. Fantasy and experience change shape. The evocative power of Singer’s inspiration acquires the stamp of reality, and reality is lifted up by dreams and imagination into the sphere of the supernatural, where nothing is impossible and nothing is sure.

Singer began his writing career in Warsaw in the years between the wars. Contact with the secularized environment and the surging social and cultural currents involved a liberation from the setting in which he had grown up – but also a conflict. The clash between tradition and renewal, between other-worldliness and pious mysticism on the one hand and free thought, doubt and nihilism on the other, is an essential theme in Singer’s short stories and novels. Among many other themes, it is dealt with in Singer’s big family chronicles – the novels The Family Moskat, The Manor and The Estate, from the 1950s and 1960s. These extensive epic works depict how old Jewish families are broken up by the new age and its demands and how they are split, socially and humanly. The author’s apparently inexhaustible psychological fantasy and insight have created a microcosm, or rather a well-populated micro-chaos, out of independent and graphically convincing figures.

Singer’s earliest fictional works, however, were not big novels but short stories and novellas. The novel Satan in Goray appeared in 1935, when the Nazi terror was threatening and just before the author emigrated to the USA, where he has lived and worked ever since. It treats of a theme to which Singer has often returned in different ways – the false Messiah, his seductive arts and successes, the mass hysteria around him, his fall and the breaking up of illusions in destitution and new illusions or in penance and purity. Satan in Goray takes place in the 17th century after the cruel ravages of the Cossacks with outrages and mass murder of Jews and others. The book anticipates what was to come in our time. These people are not wholly evil, not wholly good – they are haunted and harassed by things over which they have no control, by the force of circumstances and by their own passions – something alien but also very close.

This is typical of Singer’s view of humanity – the power and fickle inventiveness of obsession, the destructive but also inflaming and creative potential – of the emotions and their grotesque wealth of variation. The passions can be of the most varied kinds – often sexual but also fanatical hopes and dreams, the figments of terror, the lure of lust or power, the nightmares of anguish. Even boredom can become a restless passion, as with the main character in the tragicomic picaresque novel The Magician of Lublin (1961), a kind of Jewish Don Juan and rogue, who ends up as an ascetic or saint. In a sense a counterpart to this book is The Slave (1962), really a legend of a lifelong, faithful love which becomes a compulsion, forced into fraud despite its purity, heavy to bear though sweet, saintly but with the seeds of shamefulness and deceit. The saint and the rogue are near of kin.

Singer has perhaps given of his best as a consummate storyteller and stylist in the short stories and in the numerous and fantastic novellas, available in English translation in about a dozen collections. The passions and crazes are personified in these strange tales as demons, spectres and ghosts, all kinds of infernal or supernatural powers from the rich storehouse of Jewish popular belief or of his own imagination. These demons are not only graphic literary symbols but also real, tangible forces. The middle ages seem to spring to life again in Singer’s works, the daily round is interwoven with wonders, reality is spun from dreams, the blood of the past pulsates in the present. This is where Singer’s narrative art celebrates its greatest triumphs and bestows a reading experience of a deeply original kind, harrowing but also stimulating and edifying. Many of his characters step with unquestioned authority into the Pantheon of literature where the eternal companions and mythical figures live, tragic – and grotesque, comic and touching, weird and wonderful – people of dream and torment, baseness and grandeur.

Dear Mr. Singer, master and magician! It is my task and my great pleasure to convey to you the heartiest congratulations of the Swedish Academy and to ask you to receive from the hands of His Majesty the King the Nobel Prize for Literature 1978.

From Les Prix Nobel. The Nobel Prizes 1978, Editor Wilhelm Odelberg, [Nobel Foundation], Stockholm, 1979

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1978